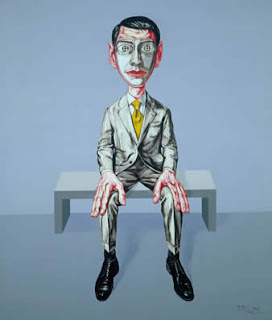

Child’s Play relives the childhood experience of unfiltered expression through artistic techniques, styles, and content. Using what initially appears to be “bad” painting, the featured artists capitalize on the accessibility and familiarity of elementary art making to address larger personal and social topics. The artists engage in energetic mark making or incorporate juvenile materials to return to past memories and evoke culturally stimulating experiences. The fluidity and freedom afforded by this form of expression helps artists access innate sentiment, ultimately indicative of the artist’s sincere motives. While the exhibited works appear less intellectually refined, their honesty and approachability ultimately elevates them to an even higher level of ingenuity and innovation.

Children function at the most basic human level, unperturbed by social consequences, judgments, or influences, yet acutely aware of relationships, attitudes, and their environment. They operate based on instinct and innate compulsion without a restricted self-consciousness. They express emotions as they arise and speak candid truths. Psychologically, children nature through various developmental stages beginning with total unconsciousness and resulting in complete, socially informed, awareness. According to Sigmund Freud, children progress from their selfishly disposed ‘id’ to the ‘ego’, a self whose consciousness is grounded in reality, and finally to the ‘superego’, driven by a sense of morality and ethicality. The inherent qualities in children, ones that encourage spontaneity and experimentation, become quelled by social norms and regulations prompting a personal negotiation with society’s pressure to conform—who are you individually and how do you exist in the world. Through maturity into adulthood, this uninhibited child-like honesty becomes latent; the oppressive impetus of society transforms ingenuity and honest expression into a sense of the “amateur.”

Yet this is not always so. Gaining popularity in the 1980s, the “Bad Painting” movement introduced a style of artwork that fought against high art intellectualism. Art encourages a freedom of expression and should, ‘bad painting’ artists believed, offer the opportunity to reveal one’s inner-self “without any grand attempt to rescue painting or make it noble.” By dismissing cultural barriers and canonical forces, these Bad artists strive to identify a greater self-awareness of internal emotions and larger cultural conditions. While some artists incorporate specific subject matter to access suppressed sentiments in a nostalgic commemoration, others re-appropriate amateur painting techniques to address the innate sensibilities of youthful freedom. While this unique style appears, to the untrained eye, unskilled and careless, it challenges viewers to “reconsider what skills are necessary to make a convincing description of the world.” These artists are radicalizing what we consider “good” or high art.

Nicola Tyson, Two Figures Touching, 2011

Oil on canvas

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

+.jpeg)

.jpeg)

,+2008,+collage..jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)