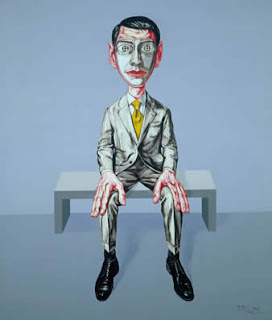

(Un)Masked explores new ways to imagine identity; rather than through literal representations of the self, this exhibition examines the hidden self, the masked self. (Un)Masked addresses issues of race, gender, and nationality to communicate larger issues within our current socio-political climate. Featuring contemporary work, this exhibition combines video art, collage, painting, and performative sculpture to illuminate the multi-faceted nature and dynamism of identity politics.

Masking, as a means of altering ones identity, functions in a much broader domain than a desire to appear unrecognizable. Masks help to conceal and transform, whether for protective, assimilation, or retaliation purposes. This act of donning a mask, however harmless one’s intentions are, always communicates a message. Not only does it expose personal identities, values, and desires, but it simultaneously illuminates the surrounding social and political context. The need to hide oneself, or acquire courage through false identity, effectively communicates which individuals and communities are being attacked, scrutinized, and/or marginalized.

Throughout the history of art, artists have and continue to utilize the mask to examine and re-evaluate displays of true identity. Masks have existed in decorative and ritualistic art practices for centuries, initially developing in Eastern cultures and gaining prominence as a Western art form. Originally, masks functioned within a ritualistic realm in which their performative function activated its meaning. Western adoption of the mask, however, emphasized its production and exhibition as its primary significance. While masks have become aesthetic artifacts for passive viewing (over active interacting), these objects continue to represent “social functions and cultural contexts.”[1] Understood as socially engaged objects, masks exist within a constant conversation between their own objectness, the individual wearer, and the cultural audience.

For the wearer, masks offer transformative properties. They provide individuals with strength, courage, and veracity, which they may find difficult to express, otherwise. Masks, in a sense, act as an outer shell, something through which individuals reveal inner desires and protect vulnerabilities. The human tendency to mask identities in order to protect or promote individual characteristics of gender, nationality, or race should come as no surprise.

With the 2012 presidential campaign evermore relevant, issues of recognition and representation lay on the forefront of American’s concerns. Candidates are debating policies and revealing their true positions on pertinent issues. Many of these issues, however, target and resonate with specific social groups, groups with already marginalized identities. In looking at the conservative leaning Republican candidate Mitt Romney, his attitudes towards minorities, specifically non-white heterosexual Christian male, surface as unjust, ignorant, and threatening. And thus, because masks are innately social, to be seen not individually experienced, people wear masks in order to experience a freedom they are otherwise denied. For women, members of the LGBTQ community, African-Americans, and so on, masks function as self protection; they allow marginalized communities to construct their own sense of power, escaping an otherwise silencing force.

All of the artists featured in this exhibition address the theme of masking, whether through physically wearing a mask or by alluding to an altered identity by means of past histories. (Un)Masked helps us understand the detriments of masking by taking a deeper look at why people do so. While acquiring a mask offers security and otherwise unfelt power, it also threatens the loss of self and connotes an environment in which individuals and larger communities feel threatened. Brian Bress’ video Family portrays the ‘idealistic’ family structure, yet one can only image that behind the masked, white, flat, characterless, vapid faces exists a more interesting and dynamic family. This reduction of self, to assimilate to convention and expectation, harms those who resist this heteronormativity by casting them as “other.” In this vein, Mitt Romney has taken opposition to same-sex marriage and civil unions, arguing for traditional marriages in which all children benefit from growing up with a mother and father.

Wangechi Mutu’s beautifully gruesome collages, furthermore, intersect perfectly with another one of Romney’s flawed principles. Romney believes that America, as a nation, needs to recognize and draw upon the skills of women and minorities, specifically in the workplace, yet fails to offer benefits or aid to them in other arenas. This idea, one that mocks the seriousness with which “women and minorities” are taken, is not only absurd but also insulting and ignorant of the struggle and progress already made. Mutu’s collages challenge this archaic viewpoint; they suggest a continuously static, even distorted awareness to issues of basic civil rights and the ongoing marginalization of identities.

The social implications of mask wearing are just as significant as the personal—lending insight to community attitudes and individual sentiments. According to Erving Goffman’s “face-work theory,” there exists a natural desire to save face, to protect oneself. Yet the face, a mask itself, changes depending on the context, audience, and social interaction. Thus, it remains essential, in looking at how people choose to mask their face, to first understand why they do so.

Brian Bress, Family (Devin, John, Jason, Lewis), 2012

High definition single-channel video (color)

15min., 41 sec., loop

.jpeg)

.jpeg)